The Adafruit Feather range is a very nice set of development boards from the NYC company. They are a good form factor (approx. 5x2cm) and stack using appropriate headers. I particularly like the Feather Huzzah and initially went for these in a big way as they fulfil a number of criteria:

- they can run MicroPython,

- the processor boards are wifi-enabled,

- and some added benefits like lots of additional addons (RTC, OLED, 7-segment displays) plus great tutorials on their web site.

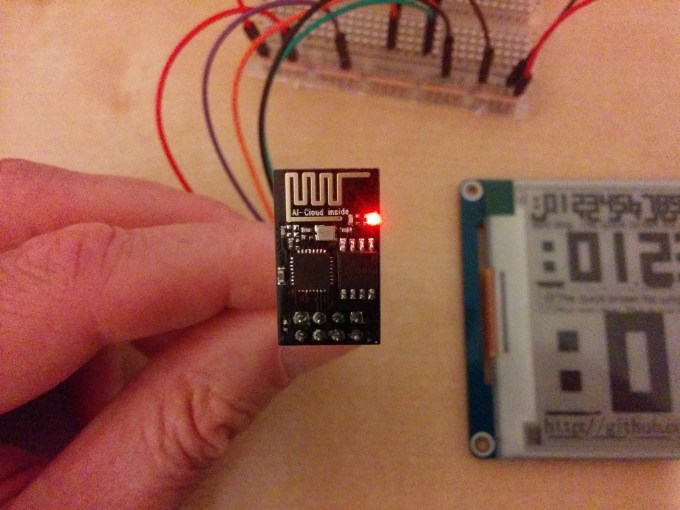

Initial and ongoing experience proved that they were very easy to work with, and they worked as expected. However, the ESP8266 wifi-enabled board does not go into a really low-power mode, consuming about ~70mA normally and the deepsleep mode requires manual intervention. That will most likely mean that I can’t use it longer term for the driver on the display, but it will prove useful as a learning exercise on the way down the power ladder.

Using Arduino IDE

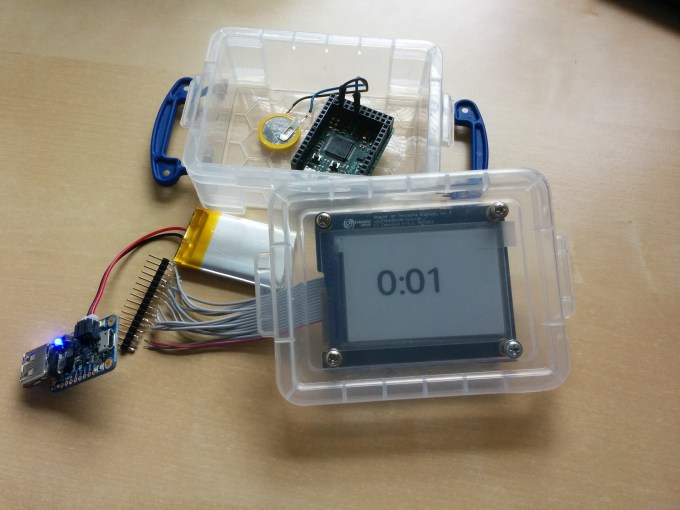

I initially started by loading MicroPython onto the board using the esptool flasher, but ran into an issue that I could not seem to find the correct pinout for the Tx/Rx. Using the ones marked on the board interferes with the USB – serial controller and you see spurious things on the link. So I backed off and re-flashed it with the Arduino IDE and a neat little bit of example clock code which works well, proving that the Tx pin works at least, and the battery powered Feather Huzzah can indeed drive the e-ink display.

MicroPython

However, using micropython proves more difficult, as I cannot seem to find the correct Tx pin for UART 1. Having flashed the 1.8.4 code level onto it using the instructions I initially tested UART(0), but as this is connected to the USB-serial chip you get all the USB traffic on those pins and so I looked to the write-only UART(1). I could not find which physical pin this was attached to even after trying all the pins one by one.